The treaties still matter, and the United States is still obligated to uphold them.

For the first time in US history, the House of Representatives will have a Cherokee delegate, as guaranteed in the 1835 Treaty of New Echota and the 1785 Treaty of Hopewell.

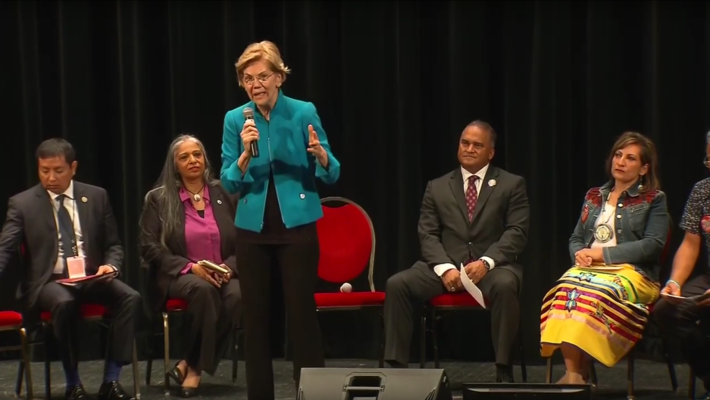

Cherokee Nation Principal Chief Chuck Hoskin, Jr. has appointed Kimberley Teehee as their first Congressional delegate. Chief Hoskin was sworn in August 14th in Tahlequah, OK. At his first State of the Nation address on August 30th, he made his intention clear. “To the Government of the United States, I say this: I’m sending a Cherokee woman to Washington D.C.”

Chief Hoskin called Teehee “extremely qualified”, and noted that the Cherokee Nation is “exercising our treaty rights and strengthening our sovereignty.”

Teehee formerly served as President Obama’s senior policy advisor for Native American affairs. She played a key role in passing the Violence Against Women Act. She also advised Rep. Dale Kildee, who co-chaired the bi-partisan Native American Caucus. She began her political career as an intern for Chief Wilma Mankiller, who made history as the first woman Cherokee Chief, and who made great strides for the nation.

Teehee said she’s “humbled” by the nomination. “This journey is just beginning and we have a long way to go to see this through to fruition,” Teehee told CNN. “However, a Cherokee Nation delegate to Congress is a negotiated right that our ancestors advocated for, and today, our tribal nation is stronger than ever and ready to defend all our constitutional and treaty rights. It’s just as important in 2019 as it was in our three treaties.”

Chief Hoskin added that “we are being thorough in terms of implementation and ask our leaders in Washington to work with us through this process and on legislation that provides the Cherokee Nation with the delegate to which we are lawfully entitled.”

Representation in Congress Guaranteed by Treaties

The United States first promised the Cherokee a Congressional delegate in 1785, with the Treaty of Hopewell. Article IX gave Congress full power to “the sole and exclusive right of regulating trade with the Indians, and managing all their affairs in such manner as they think proper.” All this, ostensibly for “the benefit and comfort” of the Cherokee people.

Should the Cherokee ever wish to have a voice in how Congress administers their “benefit and comfort”, article XII adds: “That the Indians may have full confidence in the justice of the United States, respecting their interests, they shall have the right to send a deputy of their choice, whenever they see fit, to Congress.”

Fifty years later, the Treaty of New Echota initiated Cherokee removal to Indian Country on the Trail of Tears, killing thousands. Article 7 guarantees again that “with a view to illustrate the liberal and enlarged policy of the Government of the United States towards the Indians in their removal beyond the territorial limits of the States, it is stipulated that they shall be entitled to a delegate in the House of Representatives of the United States whenever Congress shall make provision for the same.”

The Cherokee Nation is taking them up on it now because, as Chief Hoskin says, “the Cherokee Nation is today in a position of strength that I think is unprecedented in its history.”

The Position Will Likely Resemble the Non-Voting Delegates of US Territories

The treaties don’t say whether the Cherokee delegate will be a voting member of the House of Representatives. Chief Hoskin says the position will likely resemble those of the six non-voting representatives of occupied US territories: Guam, American Samoa, Puerto Rico, the US Virgin Islands, and the Northern Mariana Islands.

“I think we have to look at the roadmaps that are laid out as a suggested path to seating our delegate,” Hoskin said, “and certainly the delegates afforded the territories give us an idea of what is workable in the Congress.” These representatives can introduce legislation and advocate for their communities in debates.

The Cherokee Nation isn’t the only Native Nation to whom the United States promised a Congressional delegate. The Choctaw Nation is another example. The Treaty of Dancing Rabbit Creek, which initiated the Choctaw Trail of Tears in 1830, guaranteed “the privilege of a Delegate on the floor of the House of Representatives” for the Choctaw people, according to article XXII. This guarantee was never fulfilled, and that treaty has since been supplanted by more current ones.

The Cherokee Nation’s implementation of their right to a Congressional delegate sets a precedent that could pave the way for other tribes to send representatives to Congress, or to call for the fulfillment of other treaty rights.