Growing up a young cinephile and a closeted queer with internalized trans- and homophobia, I didn’t realize that my taste in movies was telling. Popular favorites like Alien, which buried gender politics in a space monster survival tale, and cult treasures like Glen or Glenda?, which was passable as a funny camp anomaly, populated my VHS shelves. I adored silver screen gay icons like Monty Clift and Cary Grant, pocketing their queerness as a shared secret my conservative family would never catch onto.

There are more obvious picks for great and classic queer films. I liked the happy go lucky Jules & Jim, for example. But I didn’t watch it again and again. The films I obsessed over had themes of suspicion, nightmares, and murder, an indication of just how afraid of my queerness I was. These are the films that I loved so much I could only have been a closeted queer kid growing up in a hostile environment.

The Talented Mr. Ripley

The screen drips with warm amber hues and the pace seems to linger in an eternal golden hour, creating a world you never want to leave. It’s this feeling that connects you to the antihero, psychopathic Tom Ripley, who never wants to leave his crush’s life.

Anthony Minghella’s masterful 1999 adaptation of Patricia Highsmith’s queer crime novel leaves a lot of the sexuality to implication and overtones. Highsmith, a lesbian, wrote Ripley as a gay misogynist. But Minghella’s version of the character is more ambiguous.

One of the reasons I didn’t awaken to my own gender and sexual identities earlier was that, as a high schooler in the 90s, conversations around identity were usually limited to two compartments: straight and gay. Terms like biromantic or sexually fluid were unheard of to me. So to find a nebulous screen character like Tom Ripley made my closeted, unlabeled little queer soul sing.

While John Malkovich’s later portrayal of Tom Ripley in Ripley’s Game explores the character as a steadier, icier, more mature psychopath, Damon brings us a sad puppy who only wants to be loved. He kills because he’s tormented. When I watched Ripley wrestling with his “demons,” my closeted self saw a disturbingly kindred spirit: a queer baby struggling to be free.

The Silence of the Lambs

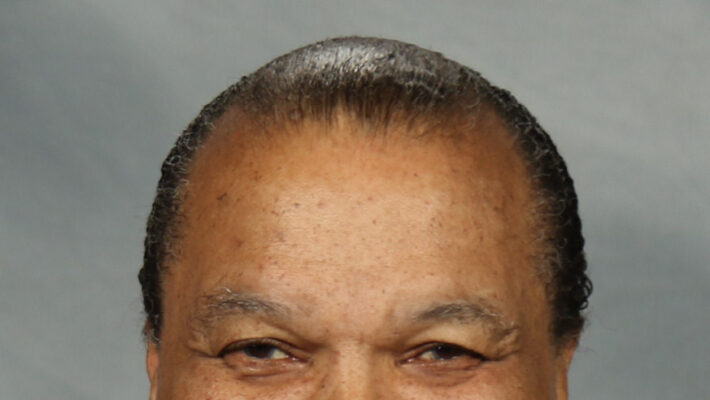

Like Tom Ripley, Hannibal Lecter is a queer literary character sprawling across multiple films, novels, writers, directors and actors. In Jonathan Demme’s 1991 adaptation of the second novel in Thomas Harris’s Hannibal trilogy, Anthony Hopkins turned in one of the screen’s towering performances, locking horns with lesbian icon Jodi Foster in an ambiguously queer but definitely sexually charged tête-à-tête.

Every conversation in the film highlights sexual power dynamics. But the most overt expressions of sexuality and power come through the film’s monster, “Buffalo Bill,” AKA Jame Gumb. Gumb is ostensibly trans, and also kidnaps and murders young women. LGBTQ activists were not quiet about the homophobia and transphobia perpetuated by linking LGBTQ identity cues with deranged criminal violence. As Silence swept the Oscars, protesters made noise in the streets. Demme tried to atone for Silence by following up with the middlebrow crowd pleaser Philidelphia, which broke ground by depicting a gay, HIV positive protagonist with humanity and compassion.

As a closeted LGBTQ youth suffering from internalized trans- and homophobia, I reveled in The Silence of the Lambs, rewatching it over and over as I did my art school homework. I lingered on the Hannibal scenes and, perhaps even more tellingly, fast forwarded through the Buffalo Bill scenes.

So who was I relating with? Hannibal for his queer sophistication? Starling for her bravery and vulnerability? Buffalo Bill for his erotic gender bending? In hindsight, I thought I was Hannibal, but I was closer to Bill, without the psychopathic violence. And coming out would require the strength and vulnerability of Starling.

Psycho

You’re starting to see the theme here. My ambiguously queer screen antiheroes were violent. I was an evangelical Christian, after all, growing up in an environment that was tremendously violent towards queer people like me. Queerness, violence and fear were inseparable in my mind.

Norman Bates is another gender-bending, transphobia-perpetuating character, this time touching on maternal rejection. The absence of maternal love is something many of us relate to, as parental rejection (or the threat of it) is such a commonly shared experience amongst LGBTQ people.

Bates is a young man lashing out at the power women have over him: his cold and controlling mother, his repressed sexual desire, and his own closeted feminine side. Relatable? Too relatable, in my case.

I idolized Hitchcock in my youth, blind to the fingerprints of misogyny all over his body of work. Shout out to Strangers on a Train, another problematic work of Hitchcockian queerness that I loved, and one that’s based on another Patricia Highsmith novel.

These movies helped me through difficult times. Thank god they’re over, and as the credits roll there’s a welcome promise of happier sequels without demons, closets, basements, or taxidermy. I’d be remiss to omit Moonlight, the film that would finally push me to flip the switch, look in the mirror and say yes, whatever it means, whatever form it takes, I am in fact an out and proud queer person. I’m not afraid of it anymore, and what a breath of fresh air it is to finally be watching happier, more affirming content like Pose.