If you haven’t encountered Tanya Tagaq yet, you’re in for a treat.

Tagaq is already established as a musician and performance artist. Her contemporary take on Inuk throat singing mixes punk aggression, goth ambience, and art rock spontaneity. Her music is often compared to Björk, and not just by happenstance. Tagaq contributed vocals to Björk’s all-vocal 2004 album Medúlla, and the two artists have toured together. But after listening to Tagaq’s guttural ferocity, Björk may sound a bit reserved and radio-friendly by comparison.

In Tagaq’s wordless Tedx talk, all the vulnerability, pain and power of indigenous womanhood seems to coalesce from the stratosphere and come rattling out of her body without any kind of filter. She holds conversational space for many spirits at once. At the end, she walks barefoot off the stage with no explanation, leaving the audience to deal on their own with the otherworldly encounter they’ve just witnessed.

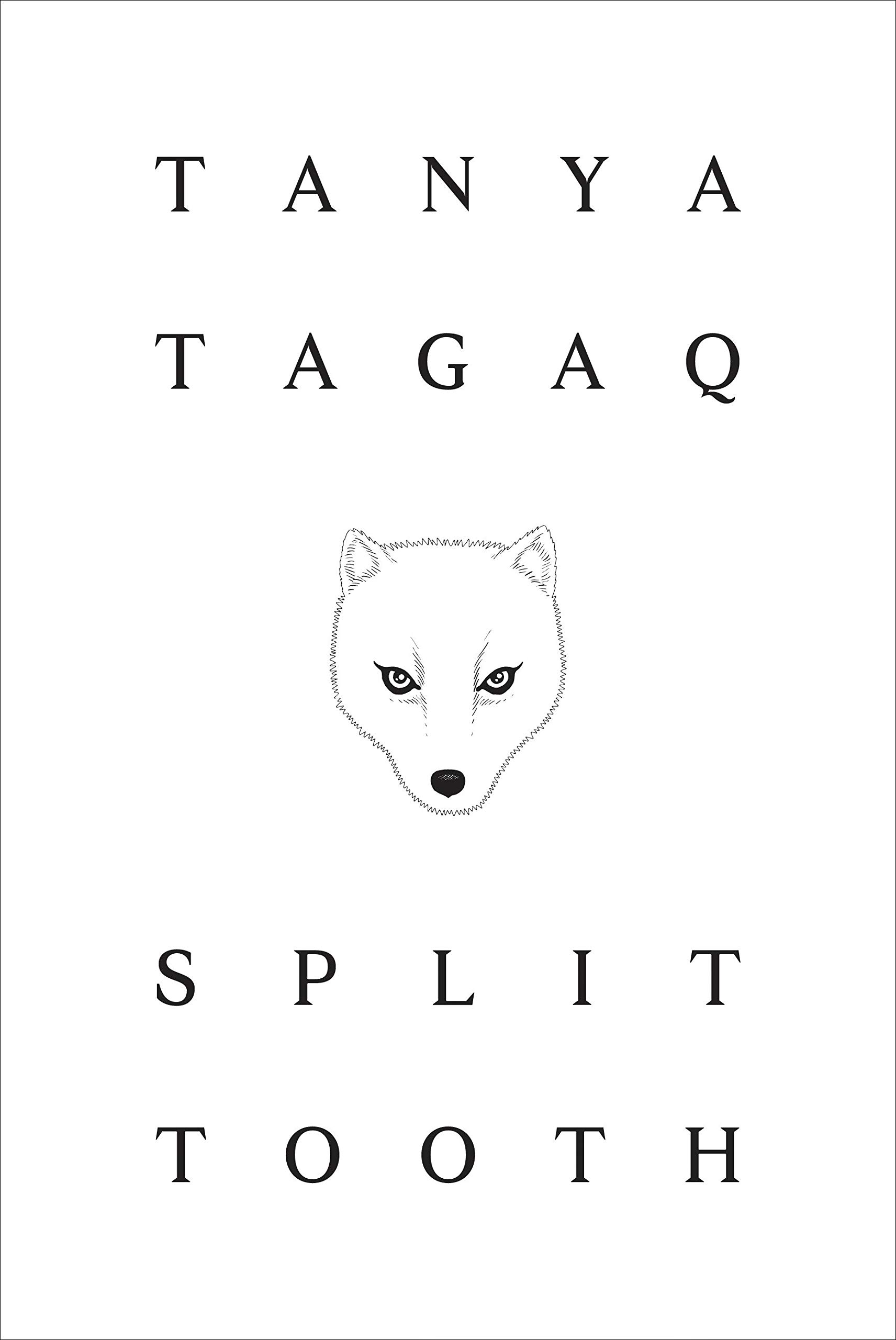

A Book Design That Previews What’s to Come

This confrontational style greets you immediately when you pick up Tagaq’s new novel, Split Tooth. Blood red page edging erupts from behind the spare, white jacket design, as if the story is bursting to get out. It calls to mind fresh meat, menstruation, and blood on arctic ice, just the kinds of images awaiting the reader inside.

Split Tooth follows the coming-of-age of a young woman on the Arctic tundra. It opens with her hiding in a closet while the drunk adults of the family blast country music from the other room until one of them opens the closet door to abuse her. In its treatment of abuse and trauma, Split Tooth is kindred to Terese Marie Mailhot’s Heart Berries, although the latter is explicitly nonfiction.

Decolonizing Lit-Fic by Blurring Genre Boundaries

With Split Tooth, you’re never really sure. It’s classified as fiction, but for most of the story you can’t tell if you’re reading a memoir or a novel. The events take place in the 70s, when the author would’ve been around the narrator’s age. It’s set in a place like the author’s home, and certainly many details must be drawn from real life.

This blurring between the western concepts of ‘fact’ and ‘fiction’ becomes important when supernatural events appear. An animal spirit needs erotic healing, or the Northern Lights induce a transformative ecstasy. The reader has to make room for the actuality of supernatural events in the indigenous experience. In this way Split Tooth confronts and dismisses colonial standards of literature and storytelling. It is neither science fiction, nor fantasy, nor literary fiction, nor magical realism, nor myth, nor memoir. It is indigenous storytelling. And the reader must deal with it, no explanation provided.

‘This Book Was Written For My Own Heart’

Tagaq revealed her uncertainty at shifting from the familiar safety of her music to the world of writing, which exposes her in a different way. “This book was written for my own heart,” Tagaq says, “and because I’m Inuk – because I’m an Indigenous woman – I’m assuming others will find alignment with it. But also, whoever wants to feel these things, to heal from it or get insight into what it feels like to be an Indigenous woman, it’s like right on.”

Tagaq is a poet (she was nominated for an Audie Award for the audiobook version of Split Tooth, which she read herself), and nearly every page offers some mind-expanding turn of language that prompts you to stare out the window a minute and reconsider your assumptions. When she describes the arctic air as “so clean you can smell the difference between smooth rock and jagged,” you can actually smell it. Even if you’ve never smelled that, or don’t know what it means.

Mind-Bending Wonder and Ordinary Adolescent Crap

Most every page will make you wince, wonder, or blurt out an unexpected laugh. Each unnamed, unnumbered chapter is postscripted with an untitled poem, which may only tangentially relate to its neighboring chapters. Occasionally you come across a simple, effective line drawing (by Fantagraphics veteran Jaime Hernandez), with a visual style masterfully reflecting Tagaq’s tone.

This formless, rhythmic structure gives the reader a feeling of being adrift, in the stars or a dream, on a choppy sea, or perhaps across the limitless ice. But Tagaq expertly guides you back to the groundwork of the story, which is the everyday crap of adolescent life: kids smoking discarded cigarette butts behind the school, crushes and catty girl fights, body insecurities. Even in its moments of gravelly realness, the surreal is never far off. These teen dramas play out in the surreal embrace of the arctic seasons, with the cabin fever of its month-long darkness, and the midnight mischief under a never-setting summer sun.

Pain and Beauty, Blood on the Ice

Split Tooth is unflinching, but Tagaq isn’t about shock value or wallowing in pain. Pain, as the narrator reminds us, is part of nature. When a fox has rabies, you shoot it. If we can survive, we survive. Nature is indifferent to suffering, and the narrator seems to be, too. Pain shares the same space as beauty, majesty, and life, like the image of blood on an endless sea of ice.

If you let this book in, it could transform you.

BjorkIndigenous Women's WritingInuitInukSplit ToothTanya TagaqThroat Singing