In decades past, we were taught to save the trees. As it turns out, it is we who need the trees to save us.

The most current report from the United Nations Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) recommends adding a billion hectares of additional forests to the earth’s surface to help slow the runaway train of atmospheric degradation.

Now, new research conducted by the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology in Zurich finds that we have enough space to plant a trillion trees, or 0.9 billion hectares of forests, an area roughly the size of the United States, without even infringing upon existing urban centers or farmlands.

We Already Have Room for All These New Forests

The team, led by ecologists Jean-Francois Bastin and Tom Crowther, examined 80,000 satellite photographs of existing forest coverage across the Earth’s surface. They looked at the remaining landmasses according to soil conditions and climate characteristics to define what kinds of forests could go where.

The nations with the most room for reforesting projects are, not surprisingly, those with an abundance of land mass: China, Russia, the US, Canada, Australia, and Brazil.

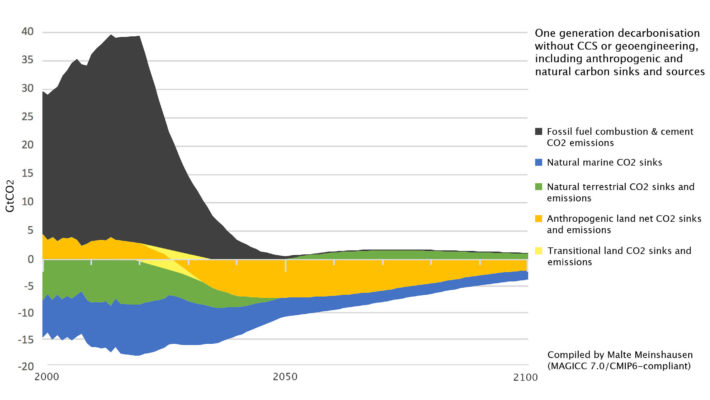

Large scale reforesting could, in the coming decades, soak up 205 gigatons of carbon from the Earth’s atmosphere. That’s about five times the amount of global carbon emissions produced during 2018, and two thirds of all human-based carbon emissions since the 1800s.

Crowther calls it “by far—by thousands of times—the cheapest climate change solution”, and the most effective one. Current trends forecast a rise of 1.5° C to arrive by 2030. Restoring a billion hectares of forest could help postpone that until 2050. It’s not a substitute for reducing fossil fuel emissions, but it will buy us some time. “None of this works without emissions cuts,” says Crowther.

Cautious Voices Remind Us There’s No Substitute for Halting Emissions

“Restoration of trees may be ‘among the most effective strategies’, but it is very far indeed from ‘the best climate change solution available’, and a long way behind reducing fossil fuel emissions to net zero,” says Oxford Professor of Geosystem Science Myles Allen, who was not involved in the study. “Yes, heroic reforestation can help, but it is time to stop suggesting there is a ‘nature-based solution’ to ongoing fossil fuel use. There isn’t. Sorry.”

Laura Duncanson, a carbon storage researcher at NASA and the University of Maryland in College Park, who was also not involved in the research, agreed. “Forests represent one of our biggest natural allies against climate change,” she said, but called the analysis “admittedly simplified” and cautioned that “we shouldn’t take it as gospel.”

New Forests Will Regenerate Biodiversity

New forests and reforestation will have positive ecological consequences beyond just creating widespread carbon sinks. They will also increase wildlife biodiversity.

Right now, 80 percent of earth’s biodiversity is protected by indigenous communities who make up only 5 percent of the human population. Reforesting and protecting biodiversity will also mean protecting indigenous people.

But even if reforestation is successful, that doesn’t mean there won’t still be fallout for human populations.

World Leaders Prepare For a ‘Climate Apartheid’

The United Nations has warned of a coming ‘climate apartheid’, wherein the wealthy have access to protection from the consequences of climate change, while the rest of the world suffers for it.

“Even if current targets are met, tens of millions will be impoverished, leading to widespread displacement and hunger,” said Philip Alston, UN Special Rapporteur on extreme poverty and human rights. “Climate change threatens to undo the last 50 years of progress in development, global health, and poverty reduction,” Alston said. “It could push more than 120 million more people into poverty by 2030 and will have the most severe impact in poor countries, regions, and the places poor people live and work.”

The irony of this is that those who are primarily responsible for causing climate change will be those who won’t have to suffer for it. “Perversely, while people in poverty are responsible for just a fraction of global emissions, they will bear the brunt of climate change, and have the least capacity to protect themselves,” Alston said. “We risk a ‘climate apartheid’ scenario where the wealthy pay to escape overheating, hunger, and conflict while the rest of the world is left to suffer.”

Many residents of Bangladesh, for example, a country under pressure from an influx of Rohingya refugees from Myanmar, will likely move from dangerously low lying areas to towns farther inland where the impact of climate change is less immediate.

The International Centre for Climate Change and Development (ICCD) in Dhaka is developing a plan for “climate-resilient, migrant-friendly cities and towns” to address the intersecting crises of climate change and refugee migration. The ICCD has identified inland towns that could triple in size and support the traditional cultural practices of migrants and refugees.

The Green Elephant in the Room

Climate-friendly cities and vast reforestation could help soften the impact of climate change. But the elephant in the room is still that the responsibility for emissions, ecological destruction and climate change falls largely on the US military and a handful of private companies. If we’re going to stop them, we’re going to have to do more than just plant a trillion trees.

But widespread reforestation, combined with intelligent urban planning to support migration, could help usher us into a more sustainable future. We spent the last two hundred years cutting down the trees. We need them to come back now.