Serving time for armed robbery really makes you think about how badly we need intersectional feminism.

Or it does if you’re Richie “Reseda” Edmond-Vargas, that is. After his arrest at age 19, Reseda started exploring the group rehabilitation programs offered to inmates. One of these was about what it means to be a man.

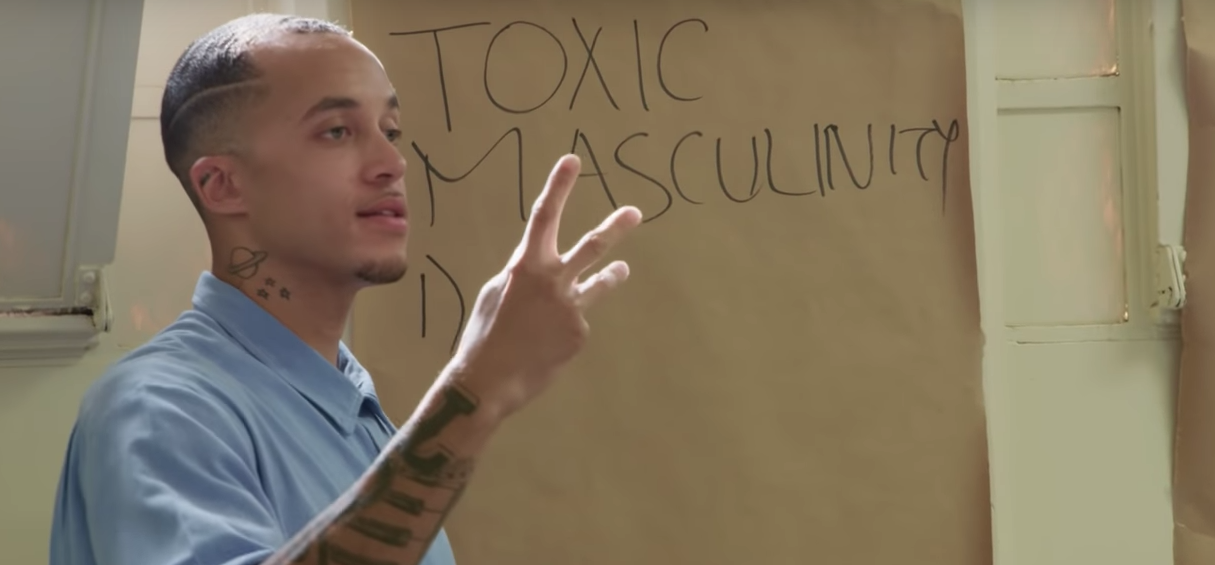

Reseda saw the curriculum as fundamentally flawed. It challenged members to abide by the law, but still upheld patriarchal ideals of manhood, like being a provider and a protector. “I saw how we as men were really destroying ourselves on some patriarchal stuff,” Reseda says. He wanted to talk explicitly about patriarchy, rape culture, toxic masculinity, and how it all has led men here—to prison sentences.

What Do You Do When Your Prison Groups Just Aren’t Confronting Patriarchy?

Since there was no platform for such a discussion, Reseda decided to pilot a one hour workshop on patriarchy, as guest speaker in the group. He based his material on The Will to Change and We Real Cool, books he’d read by Black feminism’s living legend bell hooks. He got the spot. When Reseda presented his workshop, he was laughed out of the room.

Instead of letting that stop him, he decided a one hour workshop wasn’t good enough anyway. He brainstormed with a fellow inmate in his computer class, Charles Berry, about making the material into its own 12 week group program.

And they did it. Success Stories, the name of their new group, asked incarcerated men to confront patriarchy and toxic masculinity head on, as the root of the diverse problems that had landed them in prison.

‘Dudes Would Get Verbally Violent’ When Confronted With Feminism

The inmates were not receptive. “I was terrified at first,” says Reseda. There were arguments, confrontations, even physical threats. “Dudes would get really mad,” he recalls. “Dudes would get verbally violent, and sometimes even physically threatening,” but he says a punch was never thrown. “Guys would just get in our faces. My face mostly.”

Reseda wasn’t going to let any of that discourage him either. “Getting the curriculum right took a minute. It was clumsy at first,” he says. “I also had to get off my high horse, where I saw myself as a teacher teaching all these people about patriarchy, rather than seeing myself as a patriarchal man who has to work through patriarchy by connecting with other patriarchal men.”

Eventually, Reseda and Berry ironed out the kinks, and after five or six rounds they had a curriculum that they say was reaching people—but not many. Because inmates had no real incentive to show up to courses, Success Stories’ influence was limited.

If Your Message Doesn’t Draw a Crowd, Change State Law

If you’re not inspired already, you might want to sit down.

In order to boost attendance, Reseda and Berry utilized the prison’s law library to write a bill that would incentivize participation in rehabilitation programs by offering sentence credits for attendance. It would “stop the revolving door of crime by emphasizing rehabilitation, especially for juveniles” and save the state of California tens of millions of dollars annually “by reducing wasteful spending on prisons”. Californians overwhelmingly voted in favor, and The Public Safety and Rehabilitation Act became state law in 2016. Then inmates had a reason to come to Reseda’s anti-patriarchy classes. The bill even helped Reseda shorten his own sentence so he could move on to help inmates in other prisons.

Now Reseda’s out, and just last week he officially founded Success Stories as a bona fide nonprofit. Its goal is to take his curriculum to other prison communities and stimulate discussions on toxic masculinity amongst inmates nationwide. The California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation has already offered partial funding to get the course into three state prisons, and there’s a gofundme to finance Reseda’s ambitious national reach.

Reseda First Encountered bell hooks in a Class For the ‘Bad’ Kids

How did a self-described artsy kid infatuated with the streets end up as the most outspoken feminist in the cellblock? Reseda first encountered bell hooks and the rhetoric of intersectional feminism when he was in high school. He was put in a class for “all the kids who were doing bad in school”.

Organizers Patrisse Cullors and Mark-Anthony Johnson visited to talk about mass incarceration. “They came into our science class and started explaining the school to prison pipeline, and he said ‘do you know that you guys sitting in here have a higher chance of going to prison than going to college?’ And I started paying attention. Because I knew something that they were talking about rang true for me.”

The idea was to get the kids involved in community organizing. “Just being in that organizing world, those kind of conversations were happening all the time. But that was the first time it was explicitly explained to me, and they used texts that bell hooks had written.”

A Rogue Feminist at Grover Cleveland High School

Soon Reseda was editor-in-chief of the Grover Cleveland High School newspaper, Le Sabre. A burgeoning feminist rabble rouser, he got in trouble for running a Valentine’s Day cover story about women’s issues. The headline “Have a Happy Vagina Day!” ran alongside an educational anatomical illustration, and an article calling for the destigmatization of the V-word.

“The idea came from The Vagina Monologues and Eve Ensler, who also started V-Day, in recognition of the fact that more women get date-raped on Valentine’s Day than any other day of the year,” Reseda says. “So rather than just talk about candy and bullshit, we wanted to put out an issue bringing attention to the date-rape that takes place on Valentine’s Day, as well as the taboo around the vagina in culture.”

In response, school administrators “flipped out”. Reseda describes them speeding through the hallways on little security carts trying to gather up all the newspapers before students could get them. They introduced policy that required every article to be approved by faculty ahead of press. In other words, the very institution that was supposed to be helping these kids do something positive instead of going to prison, was silencing their anti-patriarchal voices.

Reseda Credits His Work to the ‘Extremely Enlightened Women’ Who Have Helped Him

Reseda wasn’t dismayed by the authoritarian backlash of his high school administration. And he’d found a mentor in Patrisse Cullors. She was a graduate of Grover Cleveland, and worked as an addiction counsellor in the school psychologist’s office. “Watching leaders like Patrisse create organizations, watching how they move through the world, how they network, how they prioritize results over status taught me so much,” he says.

”I had extremely enlightened women in my life,” referring also to his girlfriend, Initiate Justice executive director and co-founder Taina Vargas-Edmond, whom he met as a teenager. “They called me out and made me aware of my experience. They held me to be more accountable and more emotionally available than I otherwise would have been.”

Reseda and Vargas-Edmond got married while he was in prison. He credits her with much of the insight behind the work he’s doing. “This is what enabled me to become aware of what being connected to my emotions felt like,” he says of being surrounded by powerful women before incarceration, “and the freedom of being a whole person.”

He learned the rhetoric of feminism through and through. But Reseda says he would slip right back into toxic masculine speech and behavior patterns as soon as he was back with his male friends. And he cites his “insecurity” as the force that lead him to the robberies that took him to prison shortly after graduating.

Male Violence: ‘We’re Not Just Acting Like This for No Reason’

The data on US violence shows 90 percent of homicides and 96 percent of mass shootings are committed by men. Eighty percent violent crime arrestees, and 73 percent of arrestees overall, are men. Men are 3.54 times more likely to commit suicide, and are more likely to abuse and become addicted to substances. The Federal Bureau of Prisons lists 93 percent of its inmates as male.

“We’re not just acting like this for no reason. Why do we buy into this?” Reseda asked his group during one meeting, as depicted in Contessa Graves’ CNN documentary about him. “What are some of the payoffs we get from buying into toxic masculinity?” Scattered answers from the group pop up. Being the boss. Glory. Reputation. Pride. Self esteem. Acceptance.

And what, asks Reseda, are the long term costs? “A life sentence,” says one inmate, to a ripple of wry laughter. Loneliness. Being unsatisfied. Do the payoffs seem like they’re worth the costs? Reseda says it feels like the answer is obvious. “Absolutely not. And yet we do it all the time.”

He reads a couple passages from The Will to Change. “When males are required to wear the mask of a false self, their capacity to live fully and freely is severely diminished. They cannot experience joy and they can never truly love.”

“Men who are whole can speak their fear without shame.”

bell hooksIntersectional FeminismMass IncarcerationPatriarchyPrisonRichie ResedaSchool to Prison PipelineToxic Masculinity